In this issue, I write about other ways to think about collecting art and highlight a piece in my own collection by Samantha Wall. Also a teeny weenie Damien Hirst update.

Just to let you know, I’ve been experiencing some serious issues with vertigo for the last couple of months, so it took a bit of extra time to get this newsletter finished. Hopefully, I am on the upswing, but I may be writing at a slightly slower pace for a bit. Going forward, there will be two more issues in the Welcome to Business School simulation (click here if you have no idea what I am talking about). One of them will have a participation element just for newsletter readers, then there will be a project wrap-up. After that, the newsletter will continue! I’m still going to write about art and business but will include other kinds of essays, as well as provide opportunities to participate in whatever fun (weird) art experiments I come up with. I don’t know what’s going to happen, but I am so happy you are here with me!

THE BEAUTIFUL PAINTINGS:

In the last newsletter, I was kind of snarky about Damien Hirst’s latest enterprise, The Beautiful Paintings, which were AI-assisted spin paintings created via an app. Turns out Hirst is gonna have the last laugh because the project made 20 million dollars in nine days. Sigh. (Interestingly, not very many folks went for the NFTs. Good on them.) You can read more here.

ART COLLECTING DOESN’T HAVE TO BE ABOUT MONEY:

Most of what I’ve written about so far in this newsletter has been about bad collector behavior. There is a whole industry set up to support people who view art as an investment, but none of it would exist if the ultra-rich didn’t want a fairly unregulated place to stash some cash. It doesn’t have to be this way! You can buy art because you love it!

Art advisors will often educate collectors on what a “good” collection is and steer their clients toward those pieces. (Good can mean a lot of different things in this context, but mostly it comes down to work that is popular, important, or part of what I’m calling “the contemporary canon.”) I recently went to The Broad in Los Angeles to see the William Kentridge exhibit (it was amazeballs) and wandered up to the third floor to see businessman Eli Broad’s famous art collection. I wrote a little bit about private museums a while back and how some people try to reduce their taxes by creating museums while making it hard for people to actually see the work. The Broad is not like that, and I appreciate their desire to share the collection with the public rather than have it quietly hang out in a tax haven somewhere. Too bad it kinda sucks.

It’s not that the work is bad. I was super excited to see eXelento by Ellen Gallagher, and I’d never seen any Cecily Brown paintings up close. I also feel like Mark Bradford’s work is better in person; there is no other way to experience their scale. (They’re real big.) But the exhibit doesn’t feel cohesive or demonstrative of any point of view. It mostly just feels like a big-ass trophy room. “Here are my Warhols! I gotta lotta Koons! Look at those (George) Condos!” It feels like what someone thought a good collection should be rather than the result of an individual’s passion and curiosity.

One of the reasons I think so much about the ethics of collecting is that I buy art on the regular. I am MUCH smaller scale than anyone I have talked about in this newsletter, but in reality, most collectors are more like me than Eli Broad. The main consideration I make before I buy is, “Do I want to look at this piece for a long time?” Owning a piece of art is a very different experience than checking something out in a museum or a gallery, and that difference is rooted in duration. When I own a piece, I have the opportunity to really get to know it. Art is not a static image on a wall, but a thing with meaning that can shift over time.

Even with the best of intentions, it is easy to get caught up in the less noble aspects of collecting. I buy art from living artists because I want to support them monetarily, and I try not to get just a bunch of white dude stuff. I make sure I look at a lot of different work, and there are so many wonderful pieces I could never buy everything I groove on. But what does it mean for a person like me (white-passing Mestiza) to collect work from artists of color? What does it mean to be an artist of color creating work that is mainly bought by white people? What do I do with a piece when it no longer engages me? How do I deal with competitive feelings when wanting to own a particular piece? I 100% understand how people can view art as a trophy. I have some very cool stuff in my collection, and I have found myself occasionally bragging about it. SOMETIMES I AM THE ASSHOLE. But I try not to be a douchebag. I try hard to operate ethically and with care because I am not buying lifeless things, but objects imbued with the intent of their creators. As an artist, I understand how hard it can be to let things out in the world. ANYTHING CAN HAPPEN.

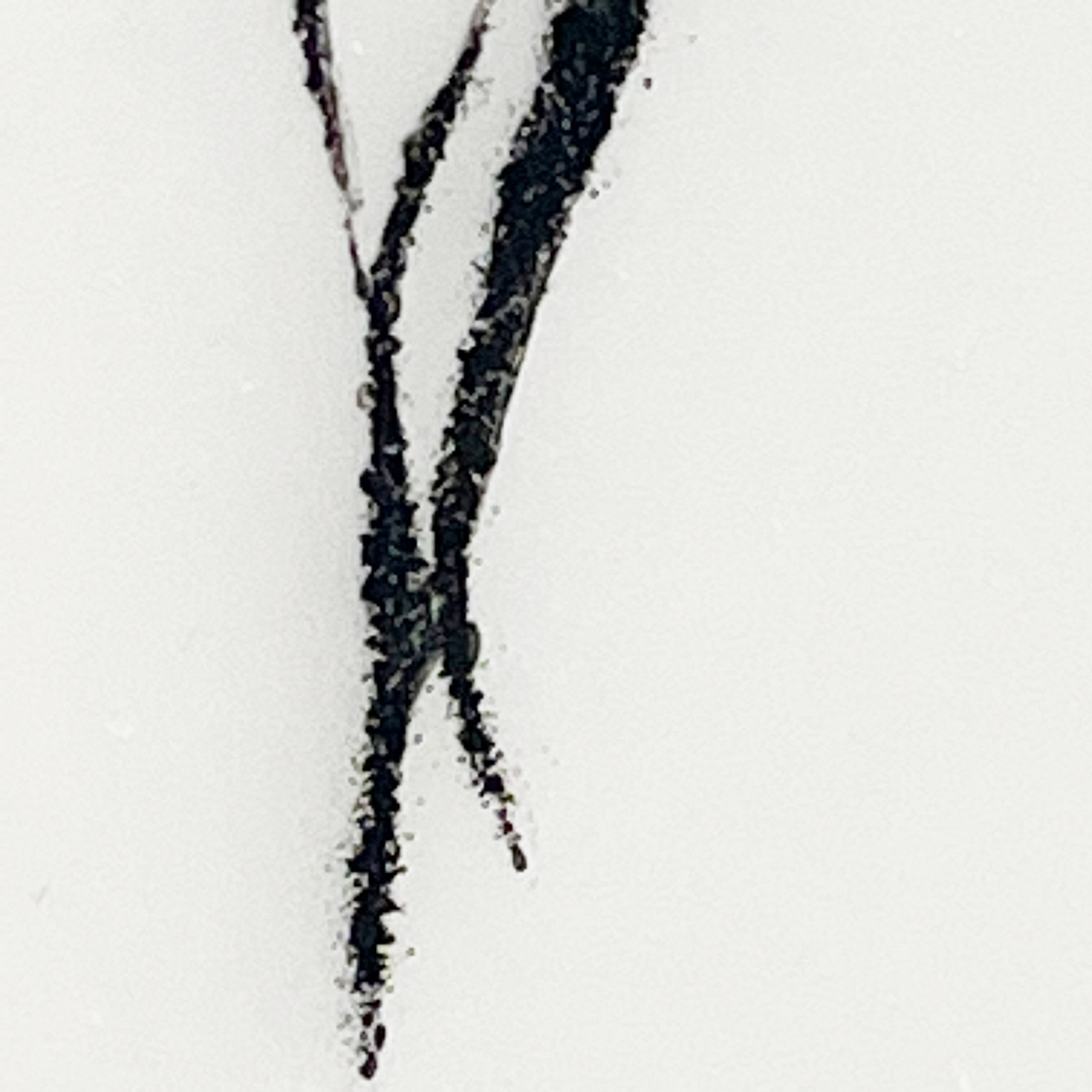

HOUSE SERPENT BY SAMANTHA WALL:

I’m gonna take a moment and talk about a piece I recently added to my collection in order to illustrate what I think a relationship with art can be. Being a viewer is different than being an artist, but I try to take some of the things I think about when making art into my experience of looking at it. In the summer of 2022, I was in Portland for my MFA program’s summer session, and our chair, Ryan Pierce, took us to the Russo Lee Gallery to see a show by Samantha Wall. He knows her, and she came and talked to us about the work from her “Beyond Bloodlines” series. I LOVED the show. Fast forward to last winter. We trekked down to Portland so I could return my school library books and check out some art. I looked at Russo Lee’s website and they had their holiday group show up, and it included a different piece by Wall, House Serpent, and we went to go check it out. It’s stunning in person, so we bought it.

So, I watch a lot of movies, and there is a 1960s series of samurai/yokai (supernatural entities) mashups from Japan that I love, and the figure in House Serpent resembles my favorite yokai, the rokurokubi, which is a woman whose neck is very long. NOW, Samantha Wall is not Japanese; she was born in South Korea, and while Korea and Japan have a tragically intertwined history, they are very much not the same place. But my attention was drawn in by the resemblance, and I knew I would have to do more research to figure out what I was actually seeing. I specifically did not ask the gallery rep Athena for more information because I wanted to experience the piece based on what I knew about Wall and what I could bring to it. I did look the piece up on Artsy.com recently, and here is what was written there:

“Wall creates portraits using ink and graphite or charcoal, to communicate the inner emotional states that separate us as individuals, while simultaneously linking us as a whole. Wall’s drawings reveal the shadow-like transparency that our bodies convey when internal emotions are difficult to penetrate and are cloaked even from our own awareness.”

What I See: House Serpent is conté crayon, charcoal, and ink on Dura-Lar and measures 49 1/2 × 35 1/2 in. It has a black shape against a white background with a woman’s face at the top looking up. It appears to be a hairy woman with a very long, thick neck. Or possibly a hairy snake with a woman’s face. (The title of the piece might indicate the latter interpretation.) The shape kind of has an S curve or rather might have one if we could see more of the figure. The face is lifted up, but the eyes are not and look directly out. (I have this hanging by a set of stairs, so I can walk up and look her in the face.) Dura-lar is a polyester film, and the drawing mediums sit on top of the surface instead of being absorbed by the paper. The figure is pretty opaque, but the face consists of stippled dots. The edges - while not exactly fuzzy - are not clean lines. There are small dots between the end of the hair/fur and the white space.

What I Think: I did some research, and Eopsin is a household goddess from a Korean religion called Muism. (I just wanna take note and say this it is also called Korean Shamanism and is considered a folk religion, and I can’t tell if that terminology is racist or not. I am an atheist and am fairly unaware of what a lot of people are up to in their church lives, but I do notice words like “shaman” and “folk” tend to be directed at not-white people in this context. I am gonna try not to sound ignorant, but I am; let me know if you have any insights into the situation.) Eopsin often takes the shape of a rat snake with ears and she is the goddess of wealth and storage in the Gasin - deities that protect the house - pantheon. Is this house serpent that house serpent? I think she might be. I am less interested in her status as a wealth protector and more in her position as a being residing between the heavenly and earthly planes. She is a goddess but resides in an animal body. My first reaction to the shape of the figure in the drawing was that it seemed too blocky, without enough variation to inhabit the white space gracefully. But now I think this body looks heavy for a reason - like it might take effort for her to move her face up toward the sky. She is both animal and divine, while at the same time being something else entirely. Each of her halves complicates the other. She cannot avoid wanting to stretch to the heavens but is weighed down by a body that is constrained by physical concerns. In the drawing, she looks neither up nor down but out. Expressionless and as opaque as her rendering, she balances both realities without giving much away.

What I Feel: I am, and probably always will be, entranced by the beauty of this piece. There is some talk against beauty in art school, probably because it seems a surface thing, but we all respond to it whether we want to admit it or not. For me, the beauty here lies in the details: the delicate rendering of the face and the small marks that exist between the solidity of the form and the lightness of the background. I really just love to look at it - to take pleasure in Wall’s draftsmanship.

But my interest and pleasure are increased because I have listened to Wall speak and read some of her writing, and I know a lot of her work explores being multiracial and multicultural. My own story is different because of my adjacency to whiteness, but I know what it is like to straddle two worlds. To inhabit the in-between spaces. To be both things and no things. I look at House Serpent and it resonates with me because I am deeply interested in how other people think about what it means to have identities that push and pull against each other.

Now, to be clear, what I have written here may not be Wall’s intent AT ALL. But there is a different alchemy between the art and the viewer. We have only the clues the artist gives us to derive intent, but in the end, we have to give ourselves to the work in order to have the kind of experience art can offer. If I did not own this piece, I probably would have looked at it for 15 minutes in the gallery, thought it was lovely, and gone about my business. But the House Serpent lives in my house. I pass by her 50 times a day. Sometimes she is a thing in the corner of my eye that I don’t take much notice of; other times I stop and take the opportunity to see something new. This is what art ownership is. It’s about giving yourself the time to really look at something someone else has made. To get to know the piece, the artist, yourself. I believe that art is in the transmission, and stuff that gets hidden in freeports to maximize investment potential isn’t art anymore; they’re lifeless money objects.

Okay! I’m done! Go look at a piece of art in your house you haven’t looked at in a while! Go buy a new piece of art! Be a repeat viewer of something in a museum! Get to know something really well! Get tired of it! Rekindle your romance! It’s so easy to just glance at something on Instagram and think you’ve really seen it. YOU HAVE NOT. Learn to look again!

So powerfully said: to own a piece of art is to experience it daily. The experience changes because we are changing. The best art gives us something new all the time.