In this issue, I am going to post a link to our online art show and talk about taxes. I WORKED VERY HARD TO MAKE THE TAX SECTION INTERESTING. I HOPE. I did not have to work so hard on the art show; people sent in amazing work.

WHAT WE CARRY: AN ONLINE ART SHOW

Inspired by Yayoi Kusama’s collaborations with Louis Vuitton and other artist licensing deals, I put out a call to you all for art with the following prompt: “If you were going to do a collaboration with a luxury brand, what would your signature bag look like, hold, or represent?” So many great things came in! And you can see them for yourself here: What We Carry

This will be up until the end of April. I hope you enjoy the show and THANK YOU SO MUCH to everyone who submitted work.

NOTHING CAN BE SAID TO BE CERTAIN, EXCEPT DEATH AND TAXES (WELL…)

I know taxes can be confusing and boring, but they’re an important part of the financialization of the art market, so I gotta talk about them. I will try to keep things simple and to the point (mostly for my benefit) and throw in some scandals to keep things interesting.

A BRIEF HISTORY OF WEALTH MANAGEMENT: First of all, I would like to recommend a book by Brooke Harrington called Capital without Borders: Wealth Managers and the One Percent. It is an ethnographic study of wealth management, and if that sounds mad boring to you, I assure you, it is not. She is a great writer, and if you have any interest in income inequality, this book is a must. What is wealth management? For a long time, I thought it was just investment dudes helping people make money in the stock market. OH NO. I mean sure, that’s a part of it, but according to Harrington “From their origins in medieval England, the practices on which wealth management is based have served two related ends: the protection of family fortunes and the reproduction of elites.”[1] Lemme break that down.

Starting back in 1095 a bunch of European Christian guys decided that Muslims should not be in charge of Jerusalem, so they started a bazillion-year war and sent a bunch of knights down to the Holy Land. (AKA The Crusades. Please take my description with a grain of salt.) At this time, most wealth was land, and women could not inherit if something happened to their husbands or fathers while they were off fighting their “holy” war. Also, unscrupulous kings could move in and take people’s stuff while they were away. So a knight could find a male friend or relation he trusted and temporarily give that guy rights to the property so everything would be safely taken care of until he came back and reassumed control.[2] BAM. Wealth management was born.

Fast forward to now! Wealth isn’t so much concentrated in land anymore; people have all sorts of assets they want to protect, including art. Most people who employ wealth managers do so because they want to keep everything they have, get more things, and make sure those things stay in their family after they die. Tax reduction is a HUGE part of this strategy, as is “avoidance of regulation, control of a family business, inheritance and succession planning, investment, and charitable giving.”[3] (“Avoidance of regulation” means “I don’t want to follow this law, so I will go somewhere I don’t have to.”) Now that art is an asset class with financial, in addition to cultural, value, strategies have arisen to both protect it from being taxed and use it as a way to decrease other taxes.

Now, there are a lot of people who think taxes are bullshit and people should get to keep most, if not all, of their money. There are also a lot of people who like roads and understand that even the most libertarian business owner uses those roads and other public benefits to run their business. We live in a country that funds our government, public infrastructure, and social safety net through taxes. When rich people don’t pay their fair share, the burden falls disproportionally on those with less to give. This means our tax base is much smaller than it should be and taxes are higher for middle and low-income people in order to make up some of the difference. This is how art tax avoidance has a real effect on our everyday lives, but it’s also something that’s hard to quantify and control because of the opacity of the art world and the squishiness of art valuations.

There is a quote I love from a New Yorker profile of dealer David Zwirner by Nick Paumgarten,

“Once you have hundreds of millions of dollars, it’s hard to know where to put it all. Art is transportable, unregulated, glamorous, arcane, beautiful, difficult. It is easier to store than oil, more esoteric than diamonds, more durable than political influence. Its elusive valuation makes it conducive to extremely creative tax accounting.”[4]

And let me tell you, there are a lot of “creative” tax strategies involving art. I’m going to lightly go through a bunch, and I am sure there are one million more I don’t know about. Let me know in the comments if you see something I’ve missed! Some of the examples I give are illegal. STAY IN SCHOOL. DON’T DO CRIME. PAY YOUR TAXES. Nobody should be paying more than they owe unless they really want to, but resorting to accounting tricks to pay nothing or less than your share is uncool. Also, just because a reduction is legal, it doesn’t mean it’s ethical.

FREEPORTS: Let’s talk about offshoring. It seems like that word would mean something happening far away - maybe an island where people are doing various complex financial things no one understands. And it can be that, but what it really is, according to my favorite writer about art and economics John Zarobell, “... can be summed up as the transfer or exchange of assets beyond regulatory authorities.”[5] So it can be companies that do shady (and aboveboard) things in the Cayman Islands with trusts and corporations, but can also be other things like freeports. A freeport is simply a big-ass warehouse that is not subject to the tax laws of the country it resides in, and they are found all over the world, including the United States. If you’ve seen the movie Tenet, a large part of the action takes place in one. Freeports began in Switzerland in the 1800s so people could store grain or whatever while it was passing through the country on the way to being bought or sold and not be subject to taxation.[6] It turns out though, one can also store other things in a tax-free warehouse, other very expensive things. If you collect art to look at, freeports would mostly serve as a place to store things that are in rotation. Museums use them all the time because they are climate controlled and secure. But if you are buying art for investment purposes, having it sent directly to a freeport means you do not have to pay sales tax. If you sell directly from a freeport, you do not have to pay capital gains taxes. You can buy and sell to your heart’s content, and as long as the items never leave the freeport under your ownership, you only pay the freeport fees. Some warehouses even offer viewing rooms, so owners can come in and look at their art, and, in many countries, opacity is the rule. No one really knows what is in a lot of these places; plenty of things get purchased and then disappear down a rabbit hole. How much art is in freeports? Who the heck knows? In 2016, 1.2 million artworks were estimated to be in just the Geneva Free Port.[7]

TRUSTS: As you may have guessed from my fascinating history of wealth management, a trust is a legal agreement where one party agrees to hold the assets of another party, and there are a lot of reasons why someone might do this. Maybe their children are dumbasses and they don’t want them to have access to the family business. Maybe they have a secret second family and take care of them through a trust so the first family doesn’t find out. (This is a real use case.) There are also other, art-related, reasons. One is tax avoidance. You can have the trust own your art, and therefore you don’t have to pay taxes on it. The trust does, but ideally, they are in a location with little to no tax burden. However, you are not supposed to have that art hanging in your house like you own it unless you rent it from the trust or make some other legal agreement. But not everyone plays fair on this. Maurizio Fabris, a London broker, bought a bunch of Banksys using a New Zealand trust company and got caught hanging the work in his house without paying any fees (or taxes.) He was charged with tax evasion in 2015.[8]

BUY MORE ART: One way to avoid paying taxes on the profits when you sell art is to immediately buy more art. It’s called a 1031 exchange.[9] Here is a really clear breakdown from Investopedia:

“A 1031 exchange is a tax break. You can sell a property held for business or investment purposes and swap it for a new one that you purchase for the same purpose, allowing you to defer capital gains tax on the sale. (Me: Capital gains are money you earn from investments. They’re taxed at a lower rate than income.)

Proceeds from the sale must be held in escrow by a third party, then used to buy the new property; you cannot receive them, even temporarily.

The properties being exchanged must be considered like-kind in the eyes of the IRS for capital gains taxes to be deferred.

If used correctly, there is no limit on how frequently you can do 1031 exchanges.”[10]

According to this, collectors can just keep plowing their profits back into new works and never have to pay tax on the sales. This only works if you don’t need that money for something else.

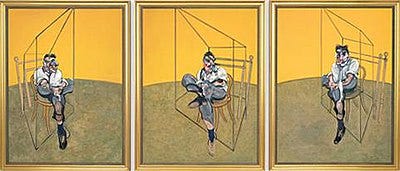

LOAN ART TO MUSEUMS IN TAX-FRIENDLY STATES: I live in Washington state, which has a sales tax. If I buy something from another state and bring it into Washington, I am supposed to pay a use tax, which serves the same purpose as a sales tax. If I want to buy a very expensive painting in another state, but I don’t want to pay any taxes, I can ship it to a museum in a state with no sales or use tax like Oregon (land of my birth) and let it chill out there until a “first use” time period is over, and I can then bring it home to bask in its glory.[11] Some states make you pay the use tax no matter how long it’s been hanging in a museum; other states drop it after a few months. In 2013, Elaine Wynn, ex-wife of the casino owner Steve Wynn, bought Francis Bacon’s triptych Three Studies of Lucian Freud for $142.4 million - at that time the highest amount ever for something sold at auction. Instead of taking it home, she lent it to the Portland Museum of Art in Oregon and saved herself about $10 million in taxes.[12] There were a lot of people who weren’t very happy about this, but it was totally legal.

MUSEUM DONATIONS: In the last newsletter, I talked a lot about the benefits of being a museum donor. A lot of museums are 501(c)(3)s, which means that if you donate money or art to them, you are eligible for a tax deduction as long as you don’t receive anything in return. But for people who don’t want to actually lose control of their favorite piece of art, but still want a tax benefit, they can give up a fractional share of a work, and the receiving museum gets to display it for their proportional share of time.[13] A more interesting, and by interesting I mean sketchy, take on museum tax benefits is when a collector turns his collection into a private museum by creating a nonprofit charitable foundation. Now there is nothing wrong with private museums if they follow the rules: they have to be open to the public and advertise. You know, act like they want people to come. But there are private museums that try to skirt those rules in order to be tax-exempt and seem to exist mostly for the owner’s benefit. In 2015, Patricia Cohen wrote this for The New York Times,

“The Brant Foundation Art Study Center — a picturesque gallery space inside a converted 1902 stone barn — is just down the road from the Greenwich, Conn., estate of its creator, Peter M. Brant, the newsprint magnate and avid art collector. There are no identifying signs for the center, whether at the turnoff on North Street, at the security gate or on the building itself, though the location is known to the art-world cognoscenti and celebrities who attend the twice-a-year gala openings, held at the private polo club next door that Mr. Brant also founded. Visits to the center itself are by appointment only.”[14]

It looks like there is now a second, newer, Brant Study Center in New York, and they appear to be a much more public-facing entity. Things are probably more open at the Greenwich outpost as well since they got called out for skirting the tax law, but it’s hard to tell from the website. Both museums are currently temporarily closed. (I’m not sure why. It’s probably innocuous.)

GIFTS: Let's say I would like to give you a very expensive painting. Maybe I’m bribing you. Maybe I just love you. Who’s to say? I bought this painting for $5,000, but now that artist’s star is rising, and I could probably sell it at auction for $40,000 or more. But gifts over $10,000 are taxable and the giver pays. But I didn’t pay that much, and if I did, it was a private sale and nobody’s business, and who is really looking anyway? Art valuation is a very slippery thing and is almost always used in the owner’s favor.

MISREPORTING VALUE: Look, something really only has a concrete, specific value when it’s sold. There is a lot of wiggle room in art valuation, and you better bet people are taking advantage of it. In 2008, the Los Angeles Times published an article about the value of art donations to museums being inflated to get bigger tax breaks. “Each year, the Internal Revenue Service audits donations claimed on only a handful of the 100,000 or more tax returns that allow art donors to reap nearly $1 billion in tax write-offs. Half of the donations checked over the last 20 years had been appraised at nearly double their actual value.”[15] THAT’S A LOT OF MONEY. People also like to undervalue work so they don’t have to pay customs fees. In 2007, a Brazilian collector was caught trying to bring an $8 million dollar Jean-Michel Basquiat painting into the U.S. with a declared value of $100. He got caught. (He had some other issues like money laundering he had to deal with as well. I’m going to talk more about money laundering in the next newsletter.)[16]

RESALE CERTIFICATES: Reseller permits let retailers and wholesalers buy items for resale without having to pay sales tax. In 2020, New York Attorney General Letitia James brought a lawsuit against Sotheby’s for filing some of these permits for collectors buying items for their personal use.[17] It is still an ongoing case, and Sotheby’s is disputing it.

COLLATERAL FOR LOANS: I have talked a lot in this newsletter about using art as collateral for loans. What are the tax implications of this? Well, I - an imaginary collector - might need money to invest in a new business. I have an art collection worth $100 million dollars, but if I sell it all, I am going to have to pay taxes unless I reinvest in more art. So I take a loan (which is not taxable income) against some pieces in my collection and do whatever with the money. This only works if the interest rate for the loan is less than the tax burden, so we’ll see how common this strategy is now that interest rates are rising.

NFTS: Nobody knows what the hell is going on with NFTs and taxes. Only a couple of states have actual policies, and the whole situation is so opaque with who the buyers and sellers are, who even knows how to report this stuff?[18] While it’s getting figured out by the feds and states, why not get into NFTs for tax-free trading? (Don’t get into NFTs.)

[1] Brooke Harrington, Capital without Borders: Wealth Managers and the One Percent (Cambridge, Mass: Harvard University Press, 2016), 10.

[2] Brooke Harrington, Capital without Borders: Wealth Managers and the One Percent, 5.

[3] Brooke Harrington, Capital without Borders: Wealth Managers and the One Percent, 7.

[4] Nick Paumgarten, “David Zwirner’s Art Empire,” The New Yorker, November 25, 2013, https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2013/12/02/dealers-hand.

[5] John Zarobell, Art and the Global Economy (Oakland, California: University Of California Press, 2017), 234.

[6] John Zarobell, Art and the Global Economy, 234.

[7] Don Thompson, The Orange Balloon Dog (Aurum, 2018), 123.

[8] Taylor Dafoe, “More than 1,600 Works of Art—Including Major Pieces by Banksy—Were Secretly Shuffled through Shell Companies, Pandora Papers Reveal,” Artnet, February 2, 2022, https://news.artnet.com/art-world/pandora-papers-art-shell-companies-2067444.

[9] “How to Avoid Taxes on Income from Selling Expensive Art?,” groco.com, May 21, 2015, https://groco.com/tax/how-to-avoid-taxes-on-income-from-selling-expensive-art/.

[10] Robert W. Wood, “10 Things to Know about 1031 Exchanges,” Investopedia, July 19, 2022, https://www.investopedia.com/financial-edge/0110/10-things-to-know-about-1031-exchanges.aspx.

[11] Graham Bowley and Patricia Cohen, “Buyers Find Tax Break on Art: Let It Hang Awhile in Oregon,” The New York Times, April 12, 2014, https://www.nytimes.com/2014/04/13/business/buyers-find-tax-break-on-art-let-it-hang-awhile-in-portland.html.

[12] Eileen Kinsella, “Museums Use Tax Breaks in Bid for Masterpieces,” Artnet, June 4, 2014, https://news.artnet.com/market/oregon-museums-dangle-tax-breaks-in-bid-for-masterpieces-30501.

[13] Heather Perlberg, “Tax Tactic of the Ultra-Wealthy: Split the Masterpiece in Two” Bloomberg, November 2, 2021, https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2021-11-02/how-do-the-rich-avoid-taxes-billionaires-use-this-art-strategy.

[14] Patricia Cohen, “Writing off the Warhol next Door,” The New York Times, January 10, 2015, sec. Business, https://www.nytimes.com/2015/01/11/business/art-collectors-gain-tax-benefits-from-private-museums.html.

[15] Jason Felch and Doug Smith, “Inflated Art Appraisals Cost U.S. Government Untold Millions,” Los Angeles Times, March 2, 2008, https://www.latimes.com/local/la-me-irs2mar02-story.html.

[16] Patricia Cohen, “Valuable as Art, but Priceless as a Tool to Launder Money,” The New York Times, May 13, 2013, sec. Arts, https://www.nytimes.com/2013/05/13/arts/design/art-proves-attractive-refuge-for-money-launderers.html.

[17] Eileen Kinsella, “The New York Attorney General Ramps up Its Investigation of Sotheby’s, Accusing the Auction House of Helping More Clients Evade Taxes,” Artnet, August 29, 2022, https://news.artnet.com/art-world/attorney-general-ramps-up-sothebys-tax-investigation-2165893.

[18] Jasmine Liu, “Pennsylvania and Washington Become the First US States to Tax NFTs,” Hyperallergic, September 6, 2022, https://hyperallergic.com/758517/pennsylvania-and-washington-become-the-first-us-states-to-tax-nfts/.

Thank you. After reading this newsletter, I checked out the audiobook ’Capital Without Borders’ from the the library.

Excellent.