In this issue, I will discuss the Masters of Fine Art: what it is, how it contributes to the financialization of art, and why I got one. Also, check out Damien Hirst’s latest nonsense after the main essay!

As a reminder, my lecture performance Global Network: Circles of Corruption in the Art Market can be found here and is a part of my MFA thesis project.

Also, did you know I have a little online gallery? It’s called Sparkle Gallery and I am currently featuring the autumnal photographs of Tom Pitts. They are pretty cool and something on the internets that isn’t depressing or shouty, so check it out! They’re here.

WHAT IS AN MFA?

You can get an MFA in both writing and visual arts, but I am only going to talk about the art one.

The Master of Fine Arts is considered a terminal degree and allows people to teach at the university level. There is a doctorate in art (Ph. D.) but not very many programs offer it, and we all make fun of people who have one. Or maybe that’s just me. I think it’s an exploration of a more theory-based practice? I dunno. I’ve only known one person who had one and that was my digital art undergrad professor back in the late 90s. For those not in the art world, there are tons of people thinking and writing about art on a more abstract philosophical level, and that art theory is part of what we nerds call “the discourse.” The MFA is usually a 2 to 3-year process where artists are able to focus on their work, gain a stronger theoretical background, and build a network of other artists, curators, and professional contacts.

WHY WOULD YOU GET ONE?

Teaching: As I wrote earlier, an MFA is the degree needed to teach studio art at a college or university, although at one time it was considered overkill. If you had a BFA (Bachelor of Fine Arts) and/or a successful practice, you were acceptable to teach. Being a studio artist isn’t like being a doctor; artists don’t actually need any theory to make good work. Doctors, on the other hand, should probably study a lot before they cut someone open. A lot of people I went to school with just wanted this piece of paper. Unfortunately, like every other major right now, art classes are often taught by adjuncts (part-timers on contract) who are scrambling to get a big enough teaching load to make a living. But it is a way for artists to earn money that - at least on the surface - seems like it might jive with being an artist, although that is not necessarily true. Being an adjunct who makes enough money to survive can be hard and doesn’t always leave people with enough time for their own practice. Also being an artist and being a teacher are completely different skill sets, and the truth is they may not always be compatible. But, getting a tenure-track job is the dream for lots of people.

Networking: When I was in grad school for my MBA, there were people in the program who were there just to expand their business network because those contacts can be very valuable to a career. A lot of artists who are “successful” (i.e. sell things and get talked about) are people with healthy networks. Most people outside of the New York art scene feeder schools (I’ll get to those later) think of this as creating a support group of people who can provide contacts, critiques, and encouragement when things get tough, and things almost always get tough for artists. In some ways, art is a perpetual rejection machine. It can be really crushing to have people hate your work, or even worse, not notice it at all. Being part of a community can help buoy people when they are having a hard time making a go of things.

Personal Enrichment: it is a privilege to have dedicated time to focus on your work. Some people just improve what they are already doing in grad school, and others reinvent their practice. (I always feel dopey calling what I do a “practice’ but it is standard in the art world, and I have gotten used to it.) Exposure to theory and other artists can also help folks understand where they sit in relation to what is happening in the larger contemporary art world.

I honestly don’t know about some people: There are always one or two folks who don’t really make much work or contribute to the experience very much. In some schools, they get weeded out, but in others, they’ll stay in the program as long as they pay their tuition and show up when they have to. It just sort of depends on the reputation of the school, what kind of program the student is in, and how desperate the school is for tuition money.

MFAS AND THE FINANCIALIZATION OF ART

Waaay back long ago, when I first started writing this newsletter, I had this to say:

“There is A LOT of art being made right now. Too much if you are trying to create a scarce resource that people will pay a lot of money for. So the market needs to figure out what is good (valuable), and since we are in a period in which there is no clear-cut definition of what that is, the market substitutes pedigree for quality (although one does not exclude the other.) If you get your degree from a school like Yale and/or get an early show at one of a very few select galleries or museums like Gagosian or the Guggenheim, you are not guaranteed anything, but you have a much greater chance of success in this market than someone coming from the outside.”

This still reads true to me after all the research I have done. While the market for ultracontemporary art (work made recently by newer artists) seems to be cooling a bit, there is still a lot of speculation in this area. Art schools like Yale, RISD, and Columbia have rich connections to the New York art scene (and places like Cal Arts to the one in Los Angeles), and so their students are more likely to receive curator and gallery interest in their MFA shows. Galleries and auction houses gotta keep pumping new stuff into the market so speculators have something to speculate on. Some people have the expectation that the MFA they get from their local university is going to help them launch an international art career. It probably won’t. And it’s not necessarily good for artists when they do get a lot of monetary attention straight out of the gate. When prices go up too fast, they are hard to maintain, and once they go down, it’s very difficult to get them back up again. Having early success in the art market is no guarantee of a sustainable career.

MY EXPERIENCE

I got my BFA in painting and printmaking in 1999 from Southern Oregon University in Ashland, OR. I had never taken any art classes before, but one was required to graduate, and my friend Tiffany suggested I take a printmaking class with her. It sounded fun and I had no idea what printmaking was, so I took it and have never looked back. (As a note, I am a horrible painter and kept turning in conceptual art projects that were not always well-received by the painting faculty.) I was a good printer technically, but the work itself was not great. I mean, it was okay, but I was by no means a baby genius, and it took me a long time (20 years) to really absorb things and learn to make work that was conceptually satisfying to me.

Like most people, I needed to pay off my student loans, so after graduation, I got a job, got my MBA, developed an autoimmune disease, dropped out of the workforce, figured out what was wrong, and got on the proper medications. I made art through most of this but wasn’t super serious about it. Eventually, I started being more focused, but I felt conceptually stuck. My friend Elan was enrolled in the low-residency program at the Pacific Northwest College of Art in Portland, OR, and suggested I might be a good fit. I applied and got in, which is not really a big surprise. While I think most people get some sort of tuition discount (aka a “merit scholarship”), there are no fully subsidized tuition slots, so there probably aren’t a million people applying.

What is a low-residency program? Existing somewhere between full-time and online programs, low-residency degrees usually require students to be on campus for only a couple of months during the year, and then the rest is done online. In my program, we met in person for 8 weeks in the summer for three years and 1 week online during January for 2 years. The rest was done at home while working with a mentor, for a total of 2 years and 4 months. During summer seminar, students took theory and professional development classes, participated in group critiques, and worked in their studios. During the not-summer season, students made art and, in their final year, wrote their thesis and prepared for an MFA show.

Was a low-residency program worth it? Yes. It suited my needs, and I am glad I did it. I have a chronic illness and would not have been able to handle school full-time. Also, this all took place during COVID-19, and I didn’t really want to be around people that much. I met a lot of good folks, my work changed radically, and I am much happier with what I am making. There was a period right before my second summer session when the chair of my program unexpectedly left (I still don’t know what exactly went down,) and things were difficult for a minute. I would have been okay with the old chair staying, but there is usually more than one way to do a thing, and I think the new chair is doing a good job. This is, however, a get-out-of-it-what-you-put-into-it kind of deal. I worked hard and it paid off for me. If I have any criticisms, it would be that I think there should be twice as much theory, and it should encompass a wider range of subjects. Most of the things we read were centered around identity, and while I think that is important, I also know that there are a lot more kinds of subject matter out there. (I did outside reading on my own, so I wasn’t exactly hurting for theory or anything.) On the downside, low-residency programs do not get as much access to the same variety of classes and resources as the full-time program does. Tuition is a little cheaper, but it’s still pretty expensive. I would advise folks to go to a full-time program if they can, but low-residency can still be worthwhile if you are willing to put in what it takes, but it can be hard to balance school, family, and work. Overall though, I recommend this particular program and would be happy to answer any questions people have about it.

PUBLIC SERVICE ANNOUNCEMENT

You do not have to get an MFA to make good art. There is no guarantee that you will be able to get a university teaching position that will pay you livable wages. Unless you are at one of the New York art market feeder schools, your chance of getting picked up by a gallery in NYC based on your MFA show is near zero. And, even if you are at one of those schools, your chances are still pretty low. MFAs are expensive, and you should not go into serious debt to get one. Schools are desperate for tuition monies and have added several different types of art graduate programs to generate more income streams. While I liked my low-residency program, we did get fewer resources and opportunities, which meant the school paid less per student. The program I was in worked for me, but I am in a privileged position and did not have to borrow against my future. If you want to get an MFA, be realistic about your goals and your ability to take on debt. Are there other things you could be doing that would give you the same results? Very few artists are making the big bucks, and others have family money, or a spouse with a high-paying job. What would a sustainable art career look like for you? Would an MFA contribute to that or make it harder?

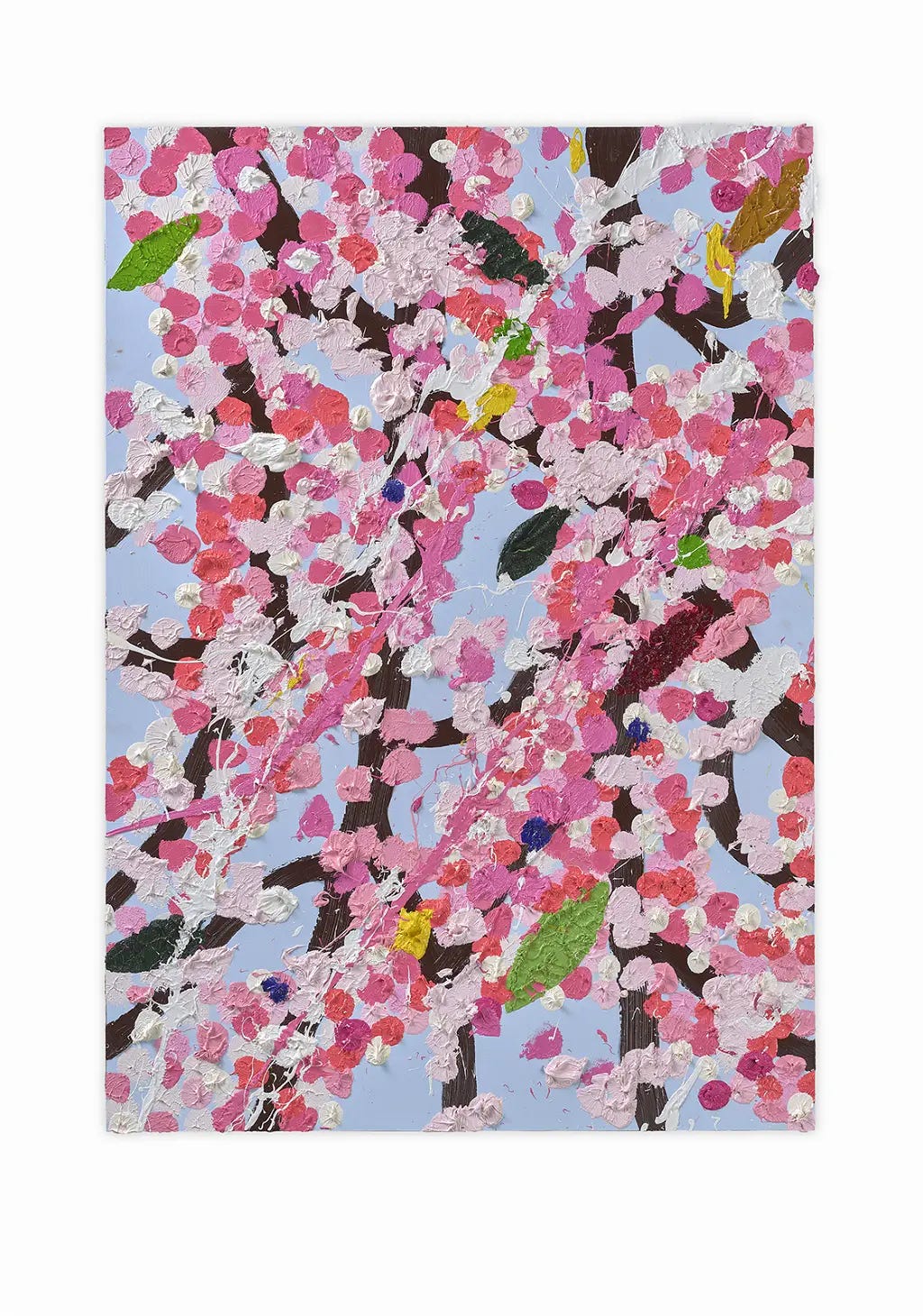

DAMIEN HIRST’S LATEST SERIES PAPER BLOSSOMS

From the sales website:

“HENI is delighted to present Paper Blossoms by Damien Hirst, a series of 900 unique original paintings on card featuring the vibrant imagery of his Cherry Blossoms paintings. The paintings are oil on card, mounted on birch ply frames, with canvas webbing around the edges. Each of the Paper Blossoms is signed and titled by Damien Hirst in oil paint on the verso.

There are 300 large Paper Blossoms, measuring 84.2 x 59.6 cm, each priced at US $45,000 (plus any applicable taxes). There are 600 small Paper Blossoms, measuring 59.6 x 42.1 cm, priced at US $25,000 (plus any applicable taxes).”

That’s a lot to pay for some hastily made crap! Don’t believe the hype! This work has no conceptual grounding and isn’t even pretty. It’s a cash grab! (See here and here for more of my rantings on Hirst if you missed them the first time around.)

Okay, that’s all! Happy Halloween! In the next newsletter, I am going to take a deep dive into Leon Black - friend of Jeffrey Epstein and former chair of the Museum of Modern Art.

FURTHER READING

https://brooklynrail.org/2013/02/artseen/alternatives

https://brooklynrail.org/2015/12/criticspage/coco-fusco

https://www.vulture.com/2013/12/saltz-on-the-trouble-with-the-mfa.html

https://www.artworkarchive.com/blog/the-great-mfa-debate-do-artists-need-graduate-school-to-succeed

https://hyperallergic.com/503928/how-do-artists-get-into-the-whitney-biennial/

Learning so much and being entertained at the same time! Thanks for the insight and biased perspective (the only type worth reading). I’m so old that I’m clueless, so any informed opinion about the current state of affairs is fascinating and illuminating.