Case Study: The Salvator Mundi

Not even Leonardo da Vinci can escape the machinations of the contemporary art market.

If you are a new reader please go here to orient yourself, as this is the second to last newsletter for my MFA thesis project, Welcome to Business School. You can also just read on since this essay can stand on its own. I will continue to write about art and business after I graduate in August, but the simulation part is almost over.

I’m doing something a little different in this issue. One of my favorite parts of getting an MBA was reading and discussing case studies. Sometimes we tried to unravel duplicitous accounting, other times we analyzed marketing problems. My favorite case studies, though, involved ethical questions. Since I don’t think you can truly have a business school simulation without at least one case study, here you go! At the end of the newsletter, I will include two opportunities for newsletter subscribers to participate beyond just reading if they are so inclined.

In this case study I will be discussing the Salvator Mundi, a painting with a heavily disputed Leonardo da Vinci attribution and the honor of being the most expensive piece of art to be sold at auction at $450 million. This is not a contemporary piece of art, so why am I writing about it? Well, older art is not immune from the machinations of the art market, and, for reasons I will discuss later, the last public sale of the piece took place during one of Christie’s contemporary art auctions. The Salvator Mundi has a very convoluted (one might say batshit) history, and while I will try to convey as much of it as I can, I will mainly be focusing on three points of ethical slipperiness. There is a lot I can’t cover because then this would be a book, and some other guy already wrote it.

THE SALVATOR MUNDI: THE SAVIOUR OF THE WORLD

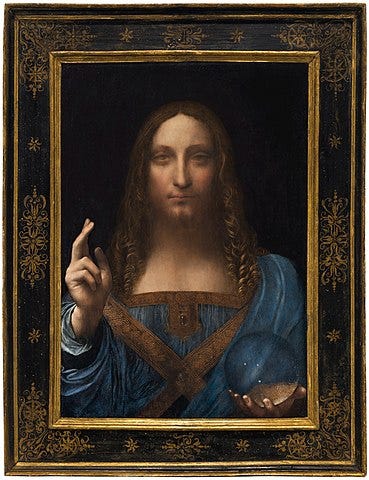

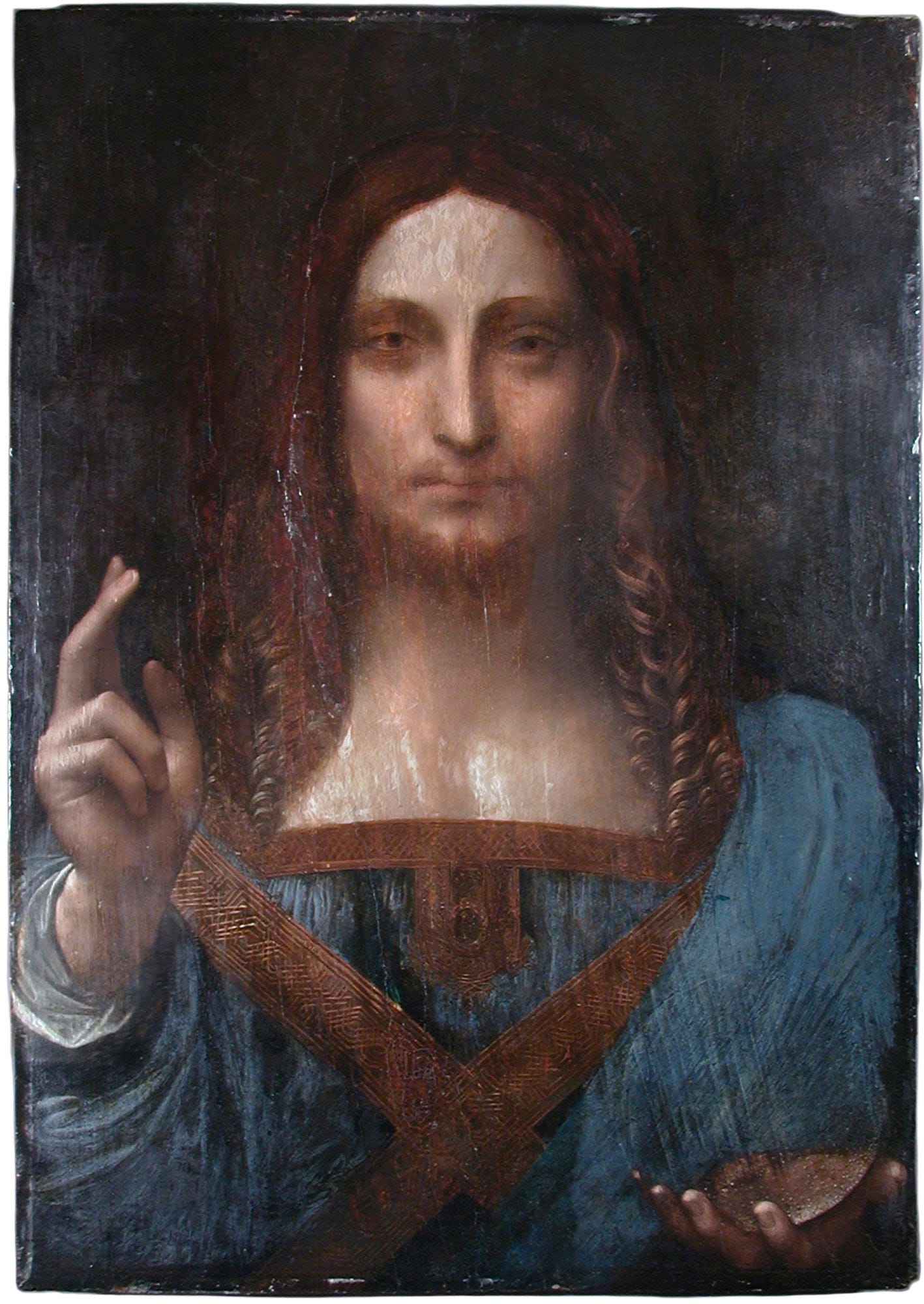

Painted sometime between 1499 and 1510 and currently (and contestedly) attributed to Leonardo da Vinci and/or his workshop, the Salvator Mundi shows Christ wearing blue and brown Renaissance garb and facing the viewer head-on. His right hand is raised with two fingers pointing up, and he is holding a clear orb in his left. (Image below.) In 2005 it was purchased from a New Orleans estate auction by art dealers Robert Simon and Alexander Parish. Both men specialized in Old Master paintings, and while they suspected this might be an interesting historical piece, they really weren’t sure what they had on their hands. Part of Parish’s job was to look through online auction listings and pull any paintings that might be of interest, and when his employer passed on the Salvator Mundi, he and Simon bought it for themselves for $1,175. Parish was looking for things he thought might be unrecognized or undervalued so he could sell them to people who would pay a lot for an ever-decreasing supply of older artworks.[1]

Two weeks after purchasing the Salvator Mundi, Robert Simon took the painting to restorer Dianne Modestini to see if she and her husband, Mario, would take a look at it. According to Ben Lewis in his book about the Salvator Mundi, The Last Leonardo: The Secret Lives of the World’s Most Expensive Painting,

“Dianne and Mario examined the painting in front of them… it had clearly been restored at some point… Christ’s face had a reddish tinge. There were crude outlines around his tired and empty eyes. The shadow underneath his chin looked like splodges of coffee stain. The chest and forehead were streaked with crumbly white deposits.”[2]

Mario Modestini, who was a Leonardo expert, remarked, “It is by a very great painter, probably a generation after Leonardo.”[3]

Dianne Modestini agreed to restore the painting and details the process on her website - and it was extensive.[4] She had to clean previous restoration efforts, including a lot of overpainting, as well as deal with worm tunneling and a faulty support. Paint had been removed, especially in the background. The face was muddy, and there were large scrapes down the right side. After cleaning and reassembling the panel, she proceeded to create what one of the painting’s co-owners, Robert Simon, referred to as a “viable work of art.”[5] It was during this process, when she was looking at the lips of the figure in the painting and comparing them to those in the Mona Lisa, that she became convinced the painting was by Leonardo.[6] Had she not continued her restoration, we would simply have what was left of the original piece, a damaged painting from the early 1500s, possibly by Leonardo Da Vinci. But Modestini - at Simon’s request - did not stop there, and much opining has gone on about that decision.

THE RESTORATION: HOW MUCH IS TOO MUCH?

That not much of the damage is visible anymore is a problem for many people. Art critic Jerry Saltz tells an amusing anecdote about seeing the painting at Christie’s before its last sale “... a well-known expert in the field leaned over and asked me a question. ‘Why is a Leonardo in a Modern and Contemporary auction?’ Before I could say, ‘Yeah! Why?’ he answered, ‘Because 90 percent of it was painted in the last 50 years.’”[7] Saltz’s buddy was not the only one who felt this way. In the film The Savior for Sale, Leonardo scholar Matthew Landrus states “Much of what we see now, of course, is repainted. Even if one calls that restoration, we also call it overpainting.”[8] (It is important here to state that overpainting can mean both painting over something and painting too much. In this instance, I believe he means both.) While many people balk at the level of restoration, others do not. Neither Sotheby’s nor Christie's nor any of the buyers thought to take issue with it. Even noted Leonardo expert Martin Kemp has no problem with the restoration as a whole.[9]

Let’s take a look at the different stages of the restoration, and you can make up your own mind.

QUESTION 1: Do you think Modestini went too far in her restoration? What might have motivated Simon and Parish to encourage her to do as much as she did? What is the purpose of art restoration? To preserve the past? To create a record of what happens over time? To capture the magic of the original artist’s touch? To prepare something for sale?

THE FIRST SALE: WHO DOES YVES BOUVIER REPRESENT?

After Dianne Modestini finished her initial restoration in 2008, Robert Simon attempted to get the Salvator Mundi attributed to Leonardo, only to start a firestorm of arguments that continues to this day. Art historian Martin Kemp believed his expertise in Leonardo gave him the ability to use “judgment by eye” to determine its origins and that it is by the master.[10] Fellow scholar Matthew Landrus disagreed. He asserted in 2018 that the majority of work on the painting was done by Leonardo’s studio assistant Bernardino Luini.[11] Expert Frank Zöllner had doubts about Leonardo’s involvement at all, suggesting that one of his students might have been responsible.[12] In 2011, Simon decided that enough people had signed off on the Leonardo attribution - even though it was still highly contested - that he could start advertising it as such. He and Parish had brought in another dealer, Warren Adelson, to help sell the piece, but even though it had been exhibited at a Leonardo show at the National Gallery in London and credited to the master, they had trouble getting anyone to make a serious offer, probably because of remaining doubts about the attribution and concerns regarding the aggressive restoration. Enter Dmitry Rybolovlev.

Rybolovlev is a Russian oligarch and billionaire who discovered a passion for art because his new house in Switzerland was set up to display art by the previous owner.[13] It probably also didn’t hurt that art is a great place to store money if you happen to have a lot of it just sitting around and worry that your enemies in your home country might want to get into your bank accounts. Rybolovlev was concerned about being taken advantage of in the art market and hired a Swiss businessman, Yves Bouvier, to help him navigate the complexities of the art world.

Bouvier grew up in a shipping family, and when he took over their company, Natural le Coultre, at 34, he decided to change its focus to art transportation and storage.[14] He also began to work behind the scenes as a dealer and decided to complement his businesses by investing heavily in freeports around the world. I talked about freeports in an earlier newsletter devoted to taxes, but they are just big-ass warehouses not subject to the tax laws of the country they reside in. If you want to buy something expensive, and you don’t want to pay taxes on it, you can put it in a freeport. As long as it stays there, it does not exist under any tax authority.

The owners of the Salvator Mundi had heard that Rybolovlev was out to build himself a world-class collection, so they reached out to him and he liked what he saw. Bouvier advised against the purchase saying “...the acquisition of this painting was not a good investment and never would be.”[15] Rybolovlev wanted to forge ahead anyway, so he asked Bouvier to negotiate the sale for him, and this is where things get tricky.

Bouvier made the purchase, and Rybolovlev was very happy with it until some interesting information got back to him. He bought the painting for $127.5 million dollars but learned that Parish, Simon, and Adelson only received $80 million. What happened?

Here are the facts:

Bouvier and Rybolovlev have no languages in common and speak through an interpreter.

Rybolovlev was under the impression that Bouvier was working as his agent for a 2% commission on sales.

Bouvier maintains that 2% was to cover expenses for the logistics of buying, transporting, and storing Rybolovlev’s art purchases.

According to Sam Knight in the New Yorker, “Major buyers typically build collections through several dealers and auction houses, knowing that they will be charged the maximum the market can bear. To protect their interests, many also employ an art adviser or consultant, who works for them and is paid a retainer or a commission—in the region of five per cent—on the works that they acquire. Very rarely are all these roles performed by one person.”[16]

Rybolovlev assumed Bouvier had negotiated the sale himself, but he had in fact sent an intermediary. The reason Rybolovlev thought Bouvier was there was because Bouvier kept sending texts about how the negotiations were going and then stated he had bought the painting for $127.5.

He had not. His representative bought the painting for him for $80 million and then he resold it to Rybolovlev with a $47.5 million markup.

When Rybolovlev found out about this he was angry because he maintains that Bouvier was working as his agent and was only entitled to 2% of $80 million.

According to Knight, “Bouvier told me that such blurring of who exactly owns what, and when a transaction occurred, is commonplace in the art market. When you walk into a gallery, you never know what the dealer is selling on consignment, what he owns outright, or how prices have been arrived at.”[17] Because of the opaque nature of the art market, Bouvier asserted his behavior followed industry norms, and Rybolovlev was at fault for not understanding how things actually work.

QUESTION 2: Rybolovlev was PISSED because he believed Bouvier had ripped him off. Who do you think is at fault here? Bouvier for trying to maximize his profit by not making it clear that he had bought the painting and then hiked up the price. Or Rybolovlev for not doing due diligence when buying something for this amount of money. It turns out this was the standard operating procedure for Bouvier, and he had sold several pieces to Rybolovlev for much more than he had paid.

THE SECOND SALE: AN OLD MASTER IN A CONTEMPORARY WORLD

Rybolovlev was livid and decided to sell off parts of his collection - including the Salvator Mundi. (He also sued Bouvier and Sotheby’s, who helped facilitate the initial purchase.) He went with Christie’s auction house, where staffer Loic Gouzer - who you may remember as one of the founders of Particle - placed the painting in the fall 2017 Contemporary and Modern evening sale. Why put it there instead of the Old Masters auction? Well, people who are likely to buy Old Masterworks tend to be educated on, well, Old Master art and would have been aware of the controversies regarding the attribution to Leonardo and the amount of restoration involved. Investors in the contemporary art market were less educated about older stuff and seemed willing to spend lots of money.[18]

Gouzer also helped orchestrate a genius ad campaign. Christie’s used a type font similar to that used in the title of The da Vinci Code movie and scrubbed all mention of the disputed attribution from the catalog and promotional materials. No longer was it considered by “Leonardo or workshop.” It was billed as “the Last Da Vinci.”[19] Before the sale, Christie’s put the painting up for public viewing and visitors were filmed looking at it. Many appeared awestruck or teary-eyed, including actor Leonardo DiCaprio. No mention was made of the fact that DiCaprio and Gouzer are good friends.[20] All-in-all, this hype enabled a $450 million (including fees) winning bid, proving Yves Bouvier wrong when he told Dmitry Rybolovlev that the Salvator Mundi would be a bad investment. While the winning bidder managed to keep their identity secret for a short while, it is generally known that it was purchased on behalf of the Saudi Prince Mohammed bin Salman (MBS), who is believed to be building a museum to show off what some call “The male Mona Lisa.”[21] If Saudi Arabia wants to position itself as a player in modern politics, soft power like owning world-class art might help people overlook some of MBS’s more unsavory aspects, like the murder of journalist Jamal Khashoggi.

QUESTION 3: Was placing the Salvator Mundi in a contemporary auction and not providing accurate information regarding the conflicting ideas about the painting’s attribution unethical? Is it incumbent on the buyer to do their research or the seller to provide every last bit of information about the work of art? How much of the value of this painting lies in people’s hopes rather than a possibly more prosaic reality?

QUESTION 4: I guess in the end, I wonder if this painting is a masterwork by Leonardo or if it is the idea of a masterwork made real by the concerted efforts of all the folks that have money or reputation on the line. I have thoughts and feelings about this, but you might feel like you need more information before you can make a decision. I have included footnotes with my sources, but there are tons of other articles on the internet if you are interested in going down this particular rabbit hole.

READER PARTICIPATION:

If you want to take a stab at actually answering one or more of these questions in a forum outside of your own head, there are two ways you can do so with the group. One is to use the comment section on Substack.

The other is to meet live with us on Zoom! If you subscribe to the newsletter and are interested in getting together with folks to discuss this case, please fill out this Google form so I can get an idea of interest and availability. During the Zoom session, I will give a teeny refresher, and then everybody will have a chance to ask questions or discuss the issues at hand. I know people don’t always read newsletters immediately, so please, if you are interested in participating, have the Google form filled out by Friday, June 16th.

[1] Ben Lewis, The Last Leonardo : The Secret Lives of the World’s Most Expensive Painting (New York: Ballatine Books, 2019), Chapter 3.

[2] Ben Lewis, The Last Leonardo : The Secret Lives of the World’s Most Expensive Painting, Chapter 10.

[3] Ben Lewis, The Last Leonardo : The Secret Lives of the World’s Most Expensive Painting, Chapter 10.

[4] “Condition and Restoration,” Salvator Mundi Revisted, accessed August 19, 2022, https://salvatormundirevisited.com/Condition-and-Restoration.

[5] Alison Cole, “New book on Leonardo’s Salvator Mundi aims to be a definitive study—but it's not the last word on the controversial painting,” The Art Newspaper, October 16, 2019, https://www.theartnewspaper.com/2019/10/16/new-book-on-leonardos-salvator-mundi-aims-to-be-a-definitive-studybut-its-not-the-last-word-on-the-controversial-painting.

[6] Ben Lewis, The Last Leonardo : The Secret Lives of the World’s Most Expensive Painting, Chapter 11.

[7] Jerry Saltz, “NOV. 14, 2017 “Christie’s Is Selling This Painting for $100 Million. They Say It’s by Leonardo. I Have Doubts. Big Doubts.”, Vulture, November 14, 2015, https://www.vulture.com/2017/11/christies-says-this-painting-is-by-leonardo-i-doubt-it.html.

[8] The Savior for Sale, directed by Antoine Vitkine (Zadig Productions, 2021) 23:00, https://www.kanopy.com/en/spl/video/12093295.

[9] Nadja Sayej, “Artistic license? Experts doubt Leonardo da Vinci painted $450m Salvator Mundi,” The Guardian, November 20, 2017, https://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/2017/nov/20/artistic-license-experts-doubt-leonardo-da-vinci-painted-450m-salvator-mundi.

[10] Eileen Kinsella, “Debunking This Picture Became Fashionable: Leonardo da Vinci Scholar Martin Kemp on What the Public Doesn’t Get About Salvator Mundi,” Artnet, June 12, 2019, https://news.artnet.com/art-world/martin-kemp-talks-salvator-mundi-new-book-1570006.

[11] Dalya Alberge, “Leonardo scholar challenges attribution of $450m painting,” The Guardian, August 6, 2018, https://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/2018/aug/06/leonardo-da-vinci-scholar-challenges-attribution-salvator-mundi-bernardino-luini.

[12] Nadja Sayej, “Artistic license? Experts doubt Leonardo da Vinci painted $450m Salvator Mundi,” The Guardian, November 20, 2017, https://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/2017/nov/20/artistic-license-experts-doubt-leonardo-da-vinci-painted-450m-salvator-mundi.

[13] The Savior for Sale, 38:38.

[14] Ben Lewis, The Last Leonardo : The Secret Lives of the World’s Most Expensive Painting, Chapter 17.

[15] Ben Lewis, The Last Leonardo : The Secret Lives of the World’s Most Expensive Painting, Chapter 17.

[16] Sam Knight, “The Art-World Insider Who Went Too Far,” The New Yorker, January 16, 2016, https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2016/02/08/the-bouvier-affair.

[17] Sam Knight, “The Art-World Insider Who Went Too Far.”

[18] Scott Reyburn, “Five Years since the $450m Salvator Mundi Sale: A First-Hand Account of the Nonsensical Auction,” The Art Newspaper, November 15, 2022, https://www.theartnewspaper.com/2022/11/15/five-years-since-the-450m-salvator-mundi-sale-a-first-hand-account-of-the-nonsensical-auction.

[19] Scott Reyburn, “Five Years since the $450m Salvator Mundi Sale: A First-Hand Account of the Nonsensical Auction.”

[20] Ben Lewis, The Last Leonardo : The Secret Lives of the World’s Most Expensive Painting, Chapter 19.

[21] “Saudi Arabia Reportedly Constructing Gallery for Leonardo’s Salvator Mundi,” www.artforum.com, October 22, 2022, https://www.artforum.com/news/saudi-arabia-said-to-be-constructing-gallery-to-house-leonardo-s-salvator-mundi-89435.