This week I try to figure out who museums are for, announce the winner of the AI art contest, and repost the open call for the What We Carry show. The intent to participate form is due by March 4 (earlier is better) and images/text are due March 6.

You may notice some format changes in this week’s newsletter. My MFA thesis is a compilation of these newsletters, and I have had to go in and footnote things after the fact. Until everything gets turned in, I’m just going to be doing one format to cut down on the work.

WHO BENEFITS FROM MUSEUMS?

In its simplest form, a museum is a collection of items made available for people other than the owner to view. Art museums, it turns out, also serve a variety of purposes beyond just letting people check out cool stuff. In his book After Art, David Joselit describes four kinds of connections an image has to create value: “Work to Citizen” “Community to Institution'', “Institution to State'', and “State To Globe”.[1] This framework applies to museums as well. (I feel like this part is more thesis-y than usual, but bear with me. It’s short, and we are gonna get to some scandals soon.)

Work to Citizen: You go to a museum and look at a picture that blows your mind. You are going to think about it for a while, and your life becomes richer.

Community to Institution: How do the community and the museum relate to each other? The museum-goer gets to enjoy culturally significant items to which they might not otherwise have access. The community supports the museum through patronage. The things in museums often cost a lot of money, so wealthy community members receive benefits by donating art or serving on the board of trustees.

Institution to State: The “state” referred to here is just the government: city, state, country, whatever. Museums are often partially state-funded, so they can position themselves as a benefit to the government, while the government in turn uses the museum to look good.

State To Globe: Suck it world. Our culture rules; your culture drools.

Almost every big city has an art museum so they will seem like an awesome place to visit, develop, and brag about. Museums employ great people - curators, art handlers, security, and public-facing folks - who work hard to create enriching experiences and are constantly coming up with new ways to make their events more accessible. It sounds pretty okay, and if that were all that was going on, I wouldn’t be asking who this really benefits. But, like everything else in the art world, there are hidden things happening that cast doubt on all those good intentions. Museums are places to look at art, but they also serve to legitimize the narrowness of the contemporary art market and benefit rich collectors. (You knew that was coming right?)

First of all, let’s look at who the real customers of museums are. Customers are people who pay money for stuff. In total, museum revenue from tickets, parking, food, etc. is only about 27% of income. And while governments provide some money, the majority of museum funding comes from donors.[2] Donors are the people who shell out cash, serve on boards, and give art. Many of them really love museums and support the mission of sharing cultural treasures, but there are benefits to donating besides warm feelings. They often have insider information regarding the market, can influence shows and collections, and get HUGE tax breaks. I’m going to talk about taxes in the next newsletter, so for now I am just going to address how museums help donors make money through information and influence.

Not just anyone can be a museum board member. While some organizations have gone out of their way to diversify their boards, it is, by and large, a pay-to-play system. In his book The Orange Balloon Dog, economist Don Thompson writes, “Board member fundraising efforts are privately described as ‘give, get, or get off.’ New board members are routinely asked for large annual contributions to operating funds, plus long-term contributions of art or capital.”[3] So why would one be a museum board member if one has to pay for the privilege? Well, there are lots of reasons; some people truly believe in the mission, want the prestige it confers, have a desire to shape the organization, and/or understand the benefits board membership can provide to their bottom line.[4]

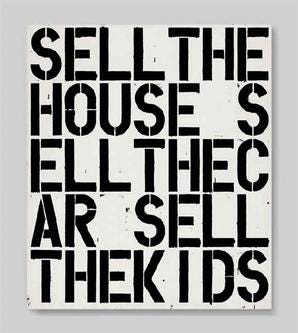

I wrote about David Ganek in an earlier newsletter. He is the former hedge fund manager who previously owned Christopher Wool’s painting Apocalypse Now. He was on the board of the Guggenheim in 2013 when the museum decided to stage a retrospective of Wool’s work, and he knew the painting would be prominently centered in the show and catalog. Once that information was put out into the world, he resigned from the board and promptly sold the painting, taking advantage of the hype around the show.[5] It is a conflict of interest to have collectors on the boards of museums, but it doesn’t violate any laws when board members act on their insider knowledge. If art wasn’t so financialized, it wouldn’t be such a big deal, but a function of museums that we haven’t really talked about yet is their power to confer value on art and how that benefits the market.

When an item is placed in a museum, there is an assumption it was carefully chosen based on merit. If something is important enough to add to the collection, it must be worth viewing. Museums create and reinforce value for the things they own, as well as other works by the artists who made those items.[6] Seeing something in a museum is how we know it is “good” or “important.” But it may not be a meritocracy at all. Donors - on the board or off - have an outsized influence on what museums show. It would be great to think that what is on display is the best our society has to offer, but there are so many other considerations that go into the decisions that put the art there. So much of what we get is based on what some finance dude who loves Jeff Koons thinks is great. Instead of seeing work that is challenging or weird or regional or nonfamous, we get stuck seeing the same artists over and over again no matter what city we are in. Because of the financialization of the art world, museums can no longer afford to buy the things they want and have to rope in donors to help out, and those folks only donate or buy things they already own or like[7]

Not only do donors get to decide which art is valuable, but they also get plenty of opportunities to make money. David Ganek’s sale of Apocalypse Now was pretty asinine, but he is not the worst offender. Back in 2009, the New Museum of Contemporary Art in Manhattan caused a scandal by announcing a show, “Skin Fruit,” comprised of the collection of one of the museum’s trustees, Dakis Joannou, and curated by the person who made him fall in love with art, Jeff Koons.[8] From The New York Times,

“‘Maybe it is a fantastic collection, but the museum is a public trust: nonprofit, tax exempt and government supported,” said Noah Kupferman, a former specialist at Sotheby’s who teaches a course called Fine Art as a Financial Asset at New York University. ‘It is supposed to be an independent arbiter of taste and art-historical value. It is not supposed to surrender itself to a trustee and donor whose collection stands to be enhanced in value by a major museum show.’”[9]

So first of all, I find it funny this quote comes from a guy who “teaches a course called Fine Art as a Financial Asset,” but it very much sums up the sentiment of the time. This show, featuring, among other artists, Christopher Wool, reinforced the idea that the things in Joannou’s collection were worthy of a museum seal of approval. This both validated the significance of the works while also increasing the status of Jeff Koons, an artist Joannou had invested in heavily. If one of the functions of museums is supposed to be elevating culturally significant art, maybe that significance should not be determined by folks who stand to profit from it. Perhaps having an outside or museum curator might have helped make this seem less prestige-grabby, but in the end, it just felt like an act of self-promotion.[10]

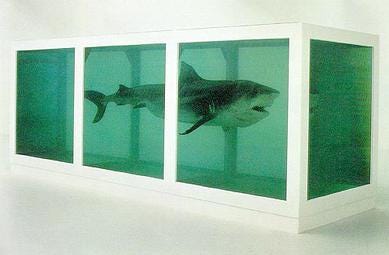

And this was not the first time (or the last) a museum allowed its reputation to suffer while increasing the fortunes of a donor. Back in 1999, the Brooklyn Museum hosted art from the collection of British businessman Charles Saatchi in the exhibition “Sensation.” Saatchi was an avid buyer of the YBAs (Young British Artists,) including Damien Hirst. I feel like maybe I pick on Koons and Hirst a lot, but honestly, they show up everywhere, and I think it’s important for readers to understand how small this world really is. Saatchi donated $160,000 to stage the show, the auction house Christie's donated $50,000, art dealers who represented some of the artists in the show donated, and even David Bowie gave $75,000 and received the rights to host images of the show on his website.[11] Did the work in this exhibition end up being important? Yes. Did it end up being so because of the efforts made by Saatchi to have his collection shown in museums like the Royal Academy of Arts in London and the Brooklyn Museum? How does any art become important? By having the people with institutional power say it is. And Saatchi did benefit from this. According to art writer Alex Greenberger while reviewing a memoir by Arnold Lehman, who was the director of the Brooklyn Museum at the time,

“And while Lehman insists that “important” works shown in “Sensation” “were never sold” in a short period after the exhibition’s run ended, the facts indicate otherwise. Hirst’s famed shark sculpture, The Physical Impossibility of Death in the Mind of Someone Living (1991), was bought by Saatchi in the early ’90s for $84,000. According to a 2009 report by Forbes, Saatchi sold it in 2005 to collector Steven A. Cohen for $13 million.”[12]

Steven Cohen, that new shark owner, currently serves on the board of the Museum of Modern Art in New York. According to ARTnews he also owns work “by Willem de Kooning, Andy Warhol, Pablo Picasso, Jasper Johns, Jeff Koons, and Jackson Pollock, among many others.”[13] He is a hedge fund manager and the majority owner of the New York Mets. (I think they are a baseball team.) He also couldn’t manage other people’s money for a couple of years because he got in trouble for insider trading. (Not surprisingly, David Ganek was also accused - although not charged - with the same thing.) In 2021, protesters objected to Choen’s position on the MOMA board, along with the tenures of a few other folks, but he is still serving.[14]

Museums have a whole host of issues. They don’t always pay workers that much, can be resistant to unionizing, take money from board members who do things like sell weapons and create opioid epidemics, and still mostly value white dudes.[15] Even the efforts to make them more accessible leave me feeling conflicted. I just read an article about how a bunch of Los Angeles museums are waiving admission fees.[16] Which is great! But they are relying on donors to make up the difference. Which is complicated! Next time you go to a museum, have a good time. But ask yourself, are they only showing the same blue-chip artists that everyone else is? Is there anything new or interesting or weird or dangerous or unpopular? Are any of the artists local? Who is that particular museum serving, your curiosity or a donor’s interests? The financialization of art really does affect what we see and who we think of as important. The real reason I always bring up Koons, Warhol, Hirst, Kusama, and Wool is that they - and artists like them - have been positioned to suck up all the oxygen in the art world. You know, I wouldn’t really care if a bunch of rich people treated art like trading cards if it didn’t have so many downstream effects. But it does, and the system is set up to reinforce their values, not some abstract ideal of what good art is. It’s okay if you want to participate in this system (or just enjoy the art,) but you should know how it works and how much we lose from it.

WINNER OF THE AI CONTEST:

And the winner of the images made from the keywords you sent in is:

I am busy working on a piece of art made using this image for the folks who voted. I’m a little behind, but it will be done soon!

CALL FOR ENTRIES (REPOST FROM LAST NEWSLETTER):

You are invited to submit an entry to an online art show, What We Carry. Technically, this is a juried show, and I am the jury, but as long as your entry observes the guidelines and isn’t offensive, I’ll accept it. YOU DO NOT HAVE TO THINK OF YOURSELF AS AN ARTIST TO ENTER. (One entry per person. Also, no fees.)

Who: You! You do need to subscribe to the newsletter or follow me on Instagram because this is meant to be an activity for our project network. However, I’m not gonna be picky about when those things happened. Please be 18 or over.

Where: I’m going to create an exhibition catalog using Twine and host it on my website. Here is an example of something I’ve made using that technology.

When: Deadline for entry is March 6th! The show will go up on my website on March 20th and will run through April.

What: Here is the prompt I would like you to consider: If you were going to do a collaboration with a luxury brand, what would your signature bag look like, hold, or represent? This is not about creating a dream bag, but a chance to explore the commodification of identities - artistic or otherwise. You can view this as a good or bad thing, have fun or be super serious. Twine can support both images and text, so you can send me a digital drawing, a scan, a photo, or a piece of writing. You can build a mock-up of a bag, draw something, make a collage, write a manifesto, or give a brief description. I am pretty open to format and subject matter; I just want a jpeg or some kind of text file emailed to me on or before March 6. What is a bag? What is a brand? Who are you on social media? What do you carry in your purse or wallet? These are questions that might help you get started.

How: Fill out this Intent to Participate on google forms. I will collect your emails to send detailed info and reminders. The last day for receiving images/text is March 6th, but the deadline to fill out the google form is March 4th. Don’t wait until the last minute! Also, filling it out doesn’t mean you are obligated to participate. We’ve all got lives and things happen. But if you think you might wanna do this, please fill out the form. Lemme know if you have any questions by responding to this email or putting them in the comments!

[1] David Joselit, After Art (New Jersey; Oxford: Princeton University Press, 2013), iBook Chapter: Formats.

[2] Don Thompson, The Orange Balloon Dog (British Columbia: Douglas and McIntyre, 2018), 163-164.

[3] Don Thompson, The Orange Balloon Dog, 166.

[4] Don Thompson, The Orange Balloon Dog, 165.

[5] Vernon Silver and James Tarmy, “The 350,000 Percent Rise of Christopher Wool’s Masterpiece Painting,” Bloomberg, October 9, 2014, https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2014-10-09/price-of-christopher-wools-apocalypse-now-soars-with-art-market.

[6] David Barstow, “Artistic Differeneces: A Special Report.; Art, Money and Control: Elements of an Exhibition,” The New York Times, December 6, 1999,

[7] John Zarobell, Art and the Global Economy (Oakland, California: University Of California Press, 2017), 46.

[8] Deborah Sontag and Robin Pogrebin, “Some Object as Museum Shows Its Trustee’s Art,” The New York Times, November 11, 2009, https://www.nytimes.com/2009/11/11/arts/design/11museum.html.

[9] Deborah Sontag and Robin Pogrebin, “Some Object as Museum Shows Its Trustee’s Art.”

[10] Jerry Saltz, “Money, Insularity, and a Huge Controversy for the New Museum,” Vulture, November 11, 2009, https://www.vulture.com/2009/11/saltz_money_insularity_and_a_h.html.

[11] David Barstow, “Brooklyn Museum Recruited Donors who Stood to Gain,” The New York Times, October 31, 1999, https://www.nytimes.com/1999/10/31/nyregion/brooklyn-museum-recruited-donors-who-stood-to-gain.html?searchResultPosition=1.

[12] Alex Greenberger, “Creating a ‘Sensation’: Arnold Lehman Recalls a 1999 Brooklyn Museum Controversy in a New Memoir,” ARTnews, October 28, 2021, https://www.artnews.com/art-news/news/arnold-lehman-sensation-brooklyn-museum-memoir-review-1234608210/.

[13] ARTnews, “Alexandra and Steven A. Cohen,” ARTnews, September 10, 2017, https://www.artnews.com/art-collectors/top-200-profiles/alexandra-and-steven-a-cohen/.

[14] Taylor Dafoe, “Activists’ Plan to Bring a March against Toxic Philanthropy inside MoMA Ended in Conflicting Accounts of Violence,” Artnet, May 3, 2021, https://news.artnet.com/art-world/1964126-1964126.

[15] Julia Halperin and Charlotte Burns, “Perceptions of Progress in the Art World Are Largely a Myth. Here Are the Facts,” Artnet, December 13, 2022, https://news.artnet.com/art-world/perceptions-of-progress-in-the-art-world-are-largely-a-myth-here-are-the-facts-2227941.

[16] Jori Finkel, “Los Angeles Museums Are Conducting the US’s Biggest Free Admission Experiment,” The Art Newspaper, February 18, 2023, https://www.theartnewspaper.com/2023/02/18/free-admission-experiment-los-angeles.