The Rise of Ultra Contemporary:

According to my sources (the one million art magazine newsletters I get in my inbox every day), ultra-contemporary is the new hotness right now. Also known as red-chip, this is work by younger artists who are going from 0 to 100 very quickly. This sounds great, especially since a bunch of these folks are white women and people of color who have historically been underrepresented, but there are real drawbacks. As auction prices get higher, so do those in the galleries, although at a slower pace. But betting on younger artists means taking a risk on unproven entities. Tastes change, fads end, and no one knows what the important stuff really is until after it’s happened. In the US, artists only get money from the original sale of a piece, so it’s important to develop a career over a number of years with steady price increases that can be sustained long-term. If valuations go too high too fast and crash, what goes down has a really hard time coming back up. (I always feel goofy talking about this market as if it were the only one. Most art I come into contact with will never have any value on the secondary market, and the artists I know have other considerations when building a career. Like can they have one.) These fluctuations can be great for speculators playing in the art market, but bad for people trying to create long-term sustainability. Many galleries try to control how much work gets out and who has access to it in order to control when pieces hit the secondary market, but sometimes an artist sells or gives away a lot of work before they get representation and then has no control over what happens to it after they start building a reputation.

I am going to give you the low down on the sales history of two paintings, one by Christopher Wool, a US artist who has been at it for a while and has demonstrated his longevity. The other is by Ghanaian artist Amoako Boafo whose star is rising, but who has encountered some issues while trying to establish himself. People are flipping his work like crazy, and while it’s helping him in the short term, it remains to be seen what the long-term effect will be. (There is some good art world gossip in both stories; after all, I did promise you scandal and excitement.)

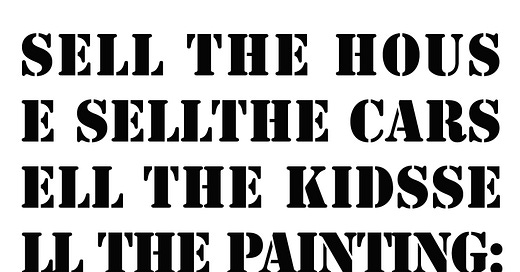

Apocalypse Now (1988) by Christopher Wool: The sales history of this painting shows a fairly typical increase in value over time for a famous artist. It took 25 years for it to appreciate in value from $7,500 to $26,000,000. (Uh, just as a reality check, most art will never be worth this much. Nor should it probably.) The amount of information about its provenance (history of ownership) is pretty unusual since most art market transactions take place behind closed doors. However, in 2014 Vernon Silver and James Tarmy wrote an amazing article for Bloomberg detailing the history of Apocalypse Now, and boy is it a great story. (It’s behind a paywall, but I will link to it at the bottom of the newsletter.) This painting is considered by some to be Wool’s masterpiece, and you can see an image of it here.

Sales History

1988: Wool shows this piece at the 303 Gallery in the East Village. Werner and Elaine Dannheisser buy out the entire show. The exact price of Apocalypse Now is unknown, but comparable sales from the same time would put it around $7,500.

1996: Elaine Dannheisser donates her collection to MOMA, but they don’t want Apocalypse Now because they already have a Wool; they could not possibly need two of them. (They are probably seething with regret every single day.)

1999: Christie's agrees to handle the auction for Apocalypse Now. Art dealer Per Skarstedt convinces them to sell to him instead for between $100,000 and $150,000. Turns out this is substantially under-market and Dannheisser is PISSED.

1999: Collector Donald Bryant Jr. Buys it for around $400,000.

2001: Bryant says his wife hates it and sells to Francois Pinault (the owner of Christie's) also for around $400,000.

2005: Hedge fund investor David Ganek buys it for $2,000,000. One thing that happens when the value of something goes over a certain amount (I don’t know the exact threshold) is the owner is able to borrow money using that item as collateral. It is common for rich people to be leveraged up to their eyeballs, so this is one reason why expensive art can be a good investment for them. Why leave money just sitting on the wall when cash can be taken out of these little metaphorical suitcases and used for a variety of other things? So, in 2006 Ganek uses Apocalypse now as collateral with Bank of America, and in 2007 with J. P. Morgan. According to the Bloomberg article, Ganek takes loans against at least 43 other works during his ownership of Apocalypse Now.

2013: Okay, here is where it gets really juicy. Ganek has been on the board of trustees for the Guggenheim since 2005, and in 2013 the museum decides to stage a retrospective of Wool’s work. (Ganek and his wife are the chairs of the exhibit’s Leadership Committee.) Apocalypse Now is going to be the star of the show and gets a big feature in the catalog. After it goes to print (this cannot be undone) Ganek resigns from the board and SELLS THE PAINTING. This is a huge scandal because its prominent placement in the show is seen as a crass move to help increase the price before Ganek sells it. No one knows who bought the painting or for how much. The Guggenheim pulls the painting from the show. (It will later get added back in 2014 when the show travels to Chicago.)

2013: Okay, so the unknown buyer immediately places the painting in Christie’s November auction, where it is bought for $26,000,000 by another unknown buyer. There is no public record of a sale after that, but this market is pretty opaque and transactions can and do happen privately. It might just be chillin’ on someone’s wall or hanging out in a warehouse; no one knows. As a reminder, Christopher Wool saw none of this money except his part of the original $7,500. He does benefit from secondary market prices though because his gallery can charge more for his art, and the length of time it took for his work to appreciate helped create a sustainable market.

The Lemon Bathing Suit (2019) by Amoako Boafo: It only took one year for The Lemon Bathing Suit to go from $22,500 to $880,971 at auction. For comparison, if you adjust for inflation (which I did on some random website) the $400,000 that Apocalypse Now sold for in 1999 would be $712,624.25 today. It took eleven years for the price to reach that amount, giving Wool a chance to slowly (I mean, not glacially slow, but still.) build a career. You can see The Lemon Bathing Suit here. There is a lot of information about this painting, but I found an article by Nate Freeman at Artnet to be especially helpful. (Linked below. No paywall.)

Sales History

2019: Boafo is represented by Bennet Roberts’ gallery in Los Angeles, Robert Projects. Roberts consigns The Lemon Bathing Suit to Jeffery Deitch, also in LA, who sells the painting to Stefan Simchowitz, a notorious art flipper. (I am thinking of devoting a whole newsletter to this guy. Some people love him, others refuse to sell to him.) Supposedly, Simchowitz promises Deitch he will keep it for his own collection rather than flip it.

2020: Simchowitz places it with Phillips in London for their February auction. It sells for $880,971 to Ari Rothstein. OR DOES IT? Well, yes it does. But the story behind that purchase is VERY convoluted. Around this time, the market for Boafo’s works is going crazy with flippers. People know a good thing when they see it and want to take advantage of the increase in prices everyone knows is coming. Boafo wants to try to put a lid on all this trading because it can hurt his long-term career prospects. So he makes a deal with Ari Rothstein and his business partner Raphael Held: they will buy The Lemon Bathing Suit for him because he doesn't have the cash, and he will give them up to $480,000 worth of art in return. He wants to take the painting off the market to try and establish some control over the number of items going up for sale. The estimation for how much this painting will sell is between $40,000 and $65,000, so Boafo isn’t too worried, but he states they agreed he will not have to pay over $480,000 if the piece goes for more than that. Whelp, Rothstein buys it for $880,974. Boafo gives them four artworks worth the agreed-upon $480,000 with the understanding that if they flip the pieces and make a profit, they will give him 20%. They immediately sell the work for $644,500, but a month later Boafo has not received his share. He also has not received The Lemon Bathing Suit. Rothstein and Held sell the painting for somewhere between $300,000 and $600,000 (I am guessing on this higher number based on another piece of data) to an unknown buyer. This person offers to sell the piece back to Boafo for $600,000 (the other piece of data), but he refuses because this experience has been disheartening and he’s over it.

There is a lot to unpack here. This all took place two years ago, and I haven’t been able to find any updates. There is a reason for that; much of the business in the art world happens behind closed doors. It sure looks like they ripped him off, but because this was a handshake deal, Boafo doesn’t have any legal recourse. (Rothstein and Held maintain their actions are perfectly legal.) It is possible things were resolved to Boafo’s satisfaction, but if so, I haven’t found any record of it. (I am also just looking things up on the internet. Let me know if you have better info.) His work is still getting flipped, and while from the outside it seems good there is so much interest in his paintings, it remains to be seen how long that interest will last.

This is happening to a lot of younger artists right now. Their work may be justifiably hot, but we won’t really know until time has passed who has sticking power. It’s hard to make a living from art, and maybe they should just take the money and run. But if they want to have a long-term career, maybe slow and steady actually does win the race. Unfortunately, they may not have any say in the matter. The loudest voices in the room appear to be those who want to invest in financial assets rather than artists’ careers. Galleries and artists are exploring options to either limit or benefit from flipping such as contracts, resale agreements, blockchain, NFTs, blacklists, buy one/donate one, and artists going directly to auction for their primary sales. It is hard to know though if these ideas will benefit artists or are just new ways for the old players to extract value from someone else’s work.

Coming Up!:

The next newsletter will be our first business simulation. We will be starting an art fund! I will explain everything!

Your Recommendations:

In the last newsletter, I asked you to help build our art network and link to folks you thought were making cool stuff. And you did! Thank you so much! Here are your recommendations:

https://zgraber.com/nft-project

https://www.instagram.com/itsreuben/

https://deborahmersky.com/beyond-beyond/

http://www.emilytolan.com/

https://tallmadgedoyle.com/

https://www.instagram.com/svetlanatrantastic/

https://www.instagram.com/helloluckycards/

https://www.instagram.com/mendrinkmen/

https://www.instagram.com/aldugggan/

https://www.instagram.com/orion_cartoonland/

https://www.instagram.com/gracemakesart/

https://www.instagram.com/rabbitandspooncreative/

https://www.instagram.com/maidrosemarian/

https://www.instagram.com/stasiaburrington/

https://www.instagram.com/schreckschreckschreckschreck/

https://www.instagram.com/boxingfoxesshop/

https://www.instagram.com/poststudiopractice/

Further Reading/Listening:

https://news.artnet.com/market/morgan-stanley-intelligence-report-triumph-contemporary-2109417

https://news.artnet.com/art-world/amoako-boafo-1910883

https://news.artnet.com/multimedia/the-art-angle-podcast-art-flippers-2195963